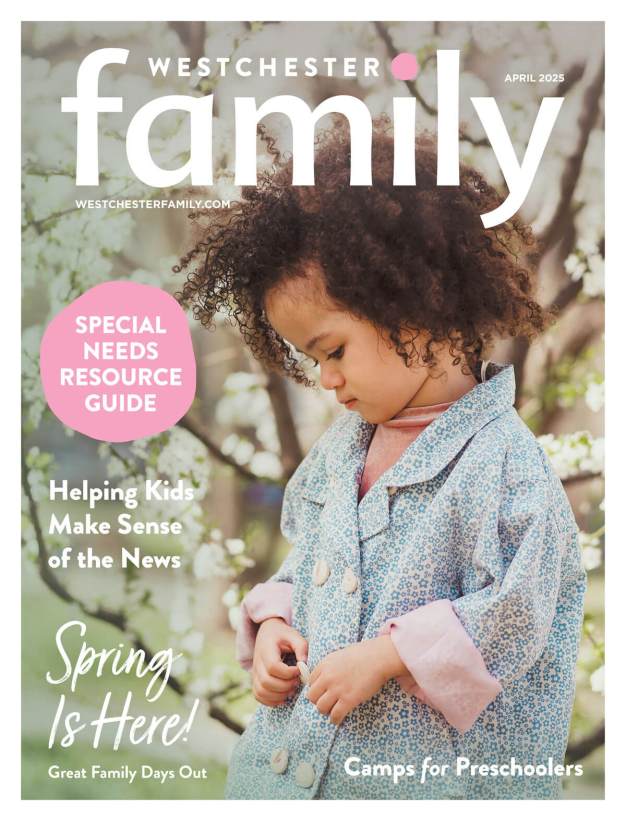

See this quilt by artist Bisa Butler at the Katonah Musem of Art from March 15 through June 14, 2020.

Four Little Girls, September 15, 1963, 2018 Cotton, silk and lace 61 x 78 in. (154.9 x 198.1 cm) Courtesy of Michelle and Pete Scantland

Bisa Butler: Portraits

Bisa Butler refers to herself as “simply an artist.” For those that have seen her works of art “simply” would be an understatement. Her art has been described as “stunning works that transform family memories and cultural practices into works of social statement.” Fortunately, Westchester families can see Butler’s first solo exhibition “Bisa Butler: Portraits” when it opens at the Katonah Museum of Art on March 15, 2020. The West Orange, New Jersey-based artist is often referred to as a fiber artist. Butler says, “I use fiber as a medium and quilt techniques, but I have been known to paint and draw as well.” It has taken years for Butler to complete the approximately 25 vivid and larger than life quilts in this exhibit. “Most of my pieces take 300 to 400 hours to complete so there are many, many long hours of work that went into this exhibition,” says Butler, who will also have a solo exhibition at the Claire Oliver Gallery in Harlem in March.

We recently spoke with Butler about her artwork and her upcoming exhibition at the Katonah Museum of Art.

Q: How would you summarize this project in your own words?

This project is a quilted fabric album of everyday people of African descent inspired by vintage photographs. My goal is to not only provide a simple snapshot of a person but also to communicate an entire story in one piece of artwork. I create portraits of people that include many clues of their inner thoughts, their heritage, their actual emotions, and even their future.

Q: Where did the idea to create a series like this originate?

I started creating this series in 2017 after I left my full-time teaching position to pursue art full time. I didn’t necessarily set out to only create images of African Americans, but I started out making portraits of the people who were in my life; my friends and family. I wanted to create images of the people in my life to honor them and show them how much I admired and loved them. All of my figures have dignity, pride, and beauty because that is the way I see them.

Q: It appears that these portraits are representations of black people from the early-mid 20th century. You’ve chosen to present them as opulent and quite regal during a historical period where society treated them as anything but. Could you shed more light on your choice in color schemes and patterns for these portraits?

I represent all of my figures with dignity, and regal opulence because that is my actual perspective of humanity. It is true that African Americans were not treated equally or even as full human beings in the past but I am showing my perspective in my artwork – it’s hard for me to imagine that anyone could meet a person and not see them the way I do. I see African Americans as the standard, not a marginalized subgroup. I actually didn’t consciously set out to portray people so regally, but others pointed out that was what I was doing.

I choose bright Technicolor cloth to represent our skin because these colors are how African Americans refer to our complexions. We may be brown, but we use terms like blue black to refer to someone who has very, very dark skin, or high yellow if the person is very fair, and red bone if the person is fair and blushes easily. I also use color to communicate a mood. If a figure is shades of cool blue, I am trying to communicate that this person has a laid back, even temperament. If a subject is bright crimson and deep burgundy, I am communicating that this person is passionate and can be fiery.

I use West African wax prints, Kente cloth, and Dutch wax prints to communicate that all of my figures are of African descent and have a long and rich history behind them. When the first Africans were forced into slavery, they were not allowed to speak their native languages, call themselves by their birth names, or keep any part of their past identity. Slavers justified their inhumane treatment of Africans by pretending that they had no past at all. I want all of my figures to have their heritage back because at the time these photos were taken many of the subjects would not have ever even referred to themselves as Africans.

Q: How would you say your own identity as an African American woman of Ghanaian heritage is represented by the patterns, colors, and materials used?

I grew up seeing my grandmother, mother, and aunties wear brightly printed African cloth. My father is from Ghana and my mother, while being African American, was raised in Morocco. My mother’s Moroccan djebellas and caftans were brightly colored silks woven with sparkly embroidery and were an ordinary mode of dress in our home. There was never a time when I did not see wax prints being worn and used as decoration at home. Kente cloth was woven in Ghana for the wealthy dignitaries and special occasions. I was raised to recognize the different colors and weaving patterns and meanings. Similar to Scottish plaids, certain Kente patterns and colors signify different tribes and regions. A bright orange red and yellow cotton silk blended Kente is from a southern Ghanaian tribe. Northern tribes wear thick cottons in bold black, white, and navy stripes.

Q: How did you become interested in working with quilting and fiber art? Why are these your chosen materials?

I became interested in working with quilting in fiber art during graduate school. I have a BFA degree in painting but I didn’t feel inspired after I finished school. I became pregnant my senior year in school and the smell of oil paint and transporting heavy canvases became overwhelming for me. I stopped painting for a few years and when I was in graduate school for an art education degree I made a small quilt, the size of an oven mitt, with a landscape design. I realized at that moment that I could use all fiber as a medium. My grandmother and mother sewed every day making clothing and home decor and they taught me the power of being able to make something for yourself. I have always loved fashion and with sewing, I could design any outfit I wanted.

Fiber and fabric appealed to me because I could manipulate them and work while sitting next to my small children. I could explore the intense colors of my background and create something new.

Q: Could you briefly explain the technique used to create the portraits?

I use the techniques taught to me while at Howard University; I start with a subject or inspiration and make a line sketch. My drawings are highly detailed because this will become my pattern. I put down layers of cloth the way a painter puts down layers of glazes. Carefully cutting each piece to match my sketch. After about 200 hours of laying down progressively smaller and smaller pieces, I stitch everything together on a long arm quilting machine. My machine is on a 12-foot-long frame and allows me to effectively draw with the threads. I use stitches to show texture like the kinks and curls of African American hair.

Q: Is there anything you consider to be important that you feel we might have missed?

I feel like I am carrying on the tradition of African American quilting into a new form of expression. It is important to learn our traditions, or they will be lost to history. African Americans originally quilted out of the necessity to stay warm in places unlike their homelands and we had very little re-sources. Our quilts were made of patches because those small rags were all we had to spare in a time when we wore our clothes until they literally fell apart.

My quilts are reminders of those times but they are artwork, not quilts to be used. The fabrics I use are new and very expensive, but the tradition is still carried on because mixed in my new fabrics are pieces of cloth given to me by my mother and grandmother. I am making something with my own two hands just like my forbearers.

See the Exhibition

Katonah Museum of Art

134 Jay St., Katonah, NY 10536

914-232-9555

katonahmuseum.org

Exhibition Dates: March 15 through June 14, 2020

Hours: Tuesday through Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Sunday, noon to 5 p.m.; closed Mondays.

Admission: $10 adults, $5 seniors, and students. Children ages 12 and under enter for free. The #ThirdThursdays program offers free admission for all on the third Thursday of every month.

Parking: Free on-site parking available.

The Learning Center: Families can enhance their experience at the Museum’s Learning Center. Drop-in to explore, play, create, and discover with free art materials during Museum hours. Projects in the Learning Center complement the exhibitions on view.

Nearby: The nearby town of Katonah offers several family-friendly restaurants. There’s also Little Joe’s, a kid-friendly bookstore serving coffee and snacks, quaint shops, and the Katonah Village Library with a Children’s Room. Cap off the day with a visit to Muscoot Farm, an early-1900’s interpretive farm, which is free and open daily to visitors.