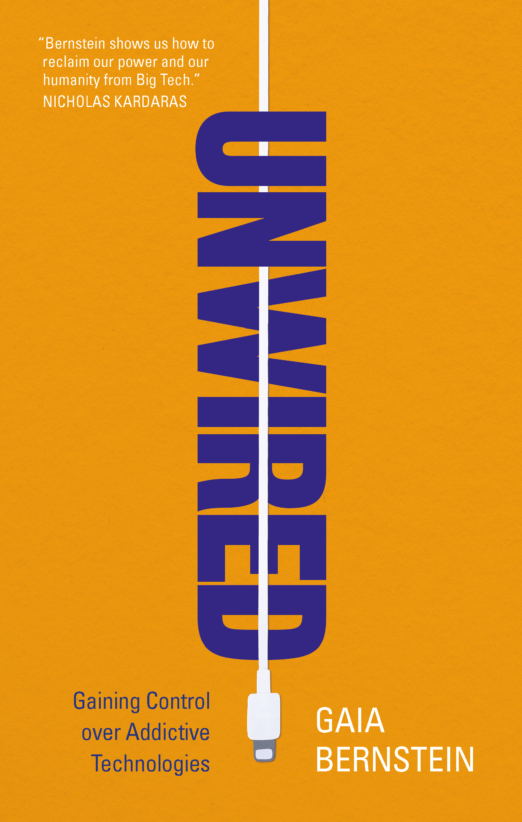

Meet Gaia Bernstein, Author of Unwired: Gaining Control over Addictive Technologies

Phones and screens are a major part of most of our lives. For our kids, phone usage has become a way of their lives that they use for everything from schooling to social interactions. To learn more about the impact of technology, we spoke with Gaia Bernstein, professor and author of the new book, Unwired: Gaining Control over Addictive Technologies” that discusses the importance of government regulation and puts pressure technology companies while highlighting the severity of this public health crisis and its impact on our kids. Read on to learn more about Gaia and Unwired below:

Westchester Family: How did the idea for “Unwired: Gaining Control over Addictive Technologies” come about?

Gaia Bernstein: Around 2015, I began noticing how my life changed. I am an academic living in NYC and a mom of three kids. I would sit down to work at a café with my laptop; cell phone and Kindle and 2-3 hours later feeling tired and depleted; I would realize little was done. When I wondered what happened to my time, I realized it was spent texting my babysitters; answering work emails and mostly constant browsing online; one click lead to another.

I started paying more attention. I noticed how I put my phone on the table whenever I sat with a friend to grab a cup of coffee; how I watched my kids’ end-of-year performances through rows of held-up phones and iPads. I also noticed my children’s lives changing. I saw children sitting in a birthday party in a row next to each other looking at their phones and not talking. Everywhere I looked I noticed we were too rarely present too often elsewhere.

I did try to make different choices for myself and my children. But by 2017, I wanted to do more than fight my personal battles. In my role as the director of the Institute for Privacy Protection at my law school, I launched an outreach program for school-aged children and their parents, which went beyond privacy to tackle technology overuse. I hoped to help kids and parents realize how much time they spent on screens and the price they paid for it. When I started speaking to parents, my main goal was to bring awareness to the topic. I wanted to write a book but it was a different book. The book I planned on writing was going to highlight the problem and explore how we can use legal tools to raise awareness of technology overuse.

When I started speaking to parents I offered self-help methods, suggesting ways to limit kids’ screen time. I suspected that technology companies purposefully designed their technologies to make sure we spend more time online. Still, I did not explicitly say this. But then things changed. Inside information from the tech titans leaked out about how the tech industry manipulates us to prolong our time online, and data accumulated about the harms of extended screen time. At the same time, the parents I lectured to felt desperate and powerless because their efforts had not helped their families. Screen time just kept going up for children and adults alike.

I realized then that real change could only come if we shifted from focusing on personal responsibility to making technology companies accountable for their addictive design choices. I ended up writing a different book, a more urgent book, a book that seeks to empower readers by describing what we could do to legally pressure the technology industry and the government to regain our autonomy for ourselves and our children.

Westchester Family: What do you hope families will get out of the book?

Gaia Bernstein: I know many people are aware that kids are spending too much time on screen, but the book describes the most updated research revealing how serious the issue is; amounting to a public health crisis for kids who spent over a decade in front screens and then the pandemic. The message is that we morally cannot neglect a whole generation of kids in front of screens. And we do not have the luxury of time to do wait.

The need for families to shift away from failing home battles (each parent with their own screen and with their children) to fighting collectively in the public sphere. We blame ourselves because the tech industry wants us to believe we are the choosers. They create this illusion of control while hooking us to screens and giving us ineffective tools like parental controls or screen time that are do not solve the problem because they are not meant to.

The goal is to exert pressure on tech companies to re-design their products to make them less addictive and to change how we use technology in physical spaces (for example classrooms). There is already a movement for change across courtrooms and legislative halls, but this is not movement for lawyers alone but for all of us especially parents who can act in their communities and schools.

Westchester Family: Why do you think screen/cell phone use is so out of control with tween/teens?

Gaia Bernstein: The tech companies took well known psychology principles and turned them into designs that are prevalent all over the Internet. They do so because this is their business model. We get products like Gmail or Instagram for free, but we pay with our time and data. So tech companies need us to stay online for as long as possible so they can collect more of our data and also so they can target advertising at us.

Kids are much more vulnerable to the impact of these designs. I will take two examples:

First, the intermittent reward model. When we get on an unpredictable schedule for food, social appreciation, money, or any reward we desire, our brains release more dopamine than when we receive rewards on a regular anticipated schedule. This is what makes the slot machine so addictive. We never know when we will win, and the coins will roll out. So, we keep pulling the handle, lured in by our brain’s expectation of a dopamine infusion. Similarly, our favorite websites, apps, and devices are so successful in retaining our attention because they imitate unpredictable rewards offered by slot machines. Notifications, like and comments are forms of intermittent reward. Kids brains are much more affected than adults by these dopamine boosts. They become more addicted.

Another set of design features targets our desire to be socially accepted and our fear of missing out (FOMO). Tweens and teens are particularly susceptible. While adults want to see what others are doing on Facebook for kids the impact of looking good and feeling left out is much greater.

But importantly, Most of today’s kids do not know another way of life. They don’t remember a world. without screens and their modes of social interactions have changed. They are much more likely to stay home in their bedrooms on their phones than go out or party. The statistics tell it all. Teens today spend a third of the time partying that their counterparts spent in the 1980s. And the number of teens who get together with their friends has been cut in half from 2000 to 2015. Phones are the chicken and the egg. They have phones so they don’t meet in person much and the less they meet the person the less natural and easy it is for them to interact this way.

Westchester Family: What can parents do about it?

Gaia Bernstein: It depends on the age of the child. When kids are young parents should resist giving kids screens as much as possible especially games, which makers often claim are educational, while they are not, and kids like them because they get these intermittent dopamine boosts.

Once kids hit middle school it becomes more complicated because their whole social life is on social networks and group texts and unilaterally isolating from their peers is not possible. While explaining to kids (if they are willing to listen) how they are manipulated by tech companies to spend so much time online could be helpful, parents should focus most of their energy outside the home.

A primary place is school. Despite all the research about the harms of screens, federal guidelines continue to promote incorporating more technology into the classroom. Since the pandemic there are even more screens, games and social networks incorporated into schoolwork. And whatever happens in school filters into the home. If Minecraft is schoolwork, it is now legitimized, and it is much harder to get a kid to stop playing it at home. In addition, screen time from school pile on to screen hours at home. Parents can be particularly effective in combatting this trend. They can be activists in individual schools or in their school district to demand that technology will only be used in the classroom if it proves to be beneficial; that screen time will be limited according to age; and that cell phones would not be used in schools even during lunch and recess.

Westchester Family: Is there a “good” age to give kids their first phone?

Gaia Bernstein: There is no magic number. Ideally, this could be delayed for as long as possible. But realistically in a world where there are no public phones, and plans are often made on the go, once a kid becomes independent and gets back from school on their own, they need a phone. For many it happens sometime in middle school.

The issue is not really the age but the fact that the mainstem phone makers are not making phones for lighter use for kids (or actually for all of us). Phones with what we need like Google Maps, texting, alarm even email and access to Internet; but no apps like social networks or games; no endless notifications and no glowing colors. Part of the idea of exerting pressure on tech companies is to get them to produce these kinds of devices. This would make the age question less crucial because we will know that giving a phone does not mean giving control. And right now, the available kiddy options are not phones teens would want to carry around.

Westchester Family: What are some general rules parents should adapt around phones/screens with their kids?

Gaia Bernstein: Parents can adopt some basic family rules, such as no phones at meals at home or when you go out (and if you take small kids out bring some crayons for them instead of an iPad and headphones, which disconnect them from the family). It is also important to remember that you are a model. Studies showed that when parents use their phone a lot so will their kids. So try to put the phone out of reach and use it when needed not as a constant distraction.

Restricting time (even through apps) is feasible for elementary school kids, some parents manage to stretch it for part of middle school. But at a certain point during middle school it becomes the center for conflict.

You can explain to them how they are manipulated by tech companies to stay online for longer (no one likes being manipulated); tell them about the studies of the harmful impact; point to them how they feel after hours online. But most importantly this point, don’t blame yourself and your kid for failing. Focus your frustration on where things can actually be changed — collectively in the public sphere.

Westchester Family: What does screen/cell phone use do to a child’s brain?

Gaia Bernstein: In recent years brain imaging studies showed what we already learnt through psychology studies. There are many troubling studies. I will two areas of study as an example, One area is cognitive development.

Neuroscientists conducting brain imaging studies examined the impact of screen time on kids’ developing brain structure. They examined the organization and myelination of white matter tracts, which influence nerve cells’ ability to transmit information faster and affect cognitive functioning. The researchers compared scans of areas in the brain related to learning in children exposed to high screen time with those of children who were not.

The researchers found that the white matter tracts of children with high screen exposure were not as structurally organized as those of the children with lower screen exposure. And, greater screen exposure was related not only to less organized white matter, but also to lower cognitive assessment scores. Scans revealed similar findings on kids ranging from 3-18, meaning that any age as kids develop, excessive screen time harms their cognitive development.

Another area is related to the impact of addiction itself. Studies were conducted on kids that were diagnosed as addicted to games. The scans indicated changes in the regions of their brains that are associated with addiction, rewards, and emotional processing, when compared to scans of a control group. These changes were connected to the intermittent reward design features of games that depend on the release of dopamine to keep the gamers hooked.

Westchester Family: Anything else to add?

Gaia Bernstein: Parents should continue the best they can at home because legal change will not come overnight. Stil, it is important to realize that there is already a movement for change taking place to pressure technology companies to redesign their products. Parents and school systems are suing social media companies and game makers for making children addicted and causing them mental harm. Legislators are constantly coming up with different bills to limit tech companies’ ability to use addictive features; many bills focus on protecting children particularly regarding use of social media. Some of these laws have already passed.

And re-designing technology isn’t the only way. It’s also about changing how we use technology in the spaces we occupy. In New York City, all three airports have iPads on every table. When my children and I wait for a flight or sit down for a meal, we cannot have a conversation because four iPads separate us; it’s impossible to avoid scrolling or playing games. These airport spaces are designed for technology overuse. But this is where all of us come in—we need to start a movement to battle technology overuse; we cannot rely on lawyers alone.

I mentioned schools before, but there is much more room for collective action. Parents are often also professionals. Business owners can influence how much people use screens on their premises, for example, restaurant owners can decide not to replace menus with QR codes, reducing the likelihood that diners will take their phones out during a meal.

Owners of online start-ups can opt for a different business model, not one that is based on advertising and user time. Technology designers can evaluate whether to design a feature whose main goal is to keep users online for longer, such as a feature designed to give us irregular dopamine boosts. We have many options to make a collective impact and it is possible to change norms and businesses.

Get the book here.